Study reviews satellite data to measure methane emissions

February 11, 2022

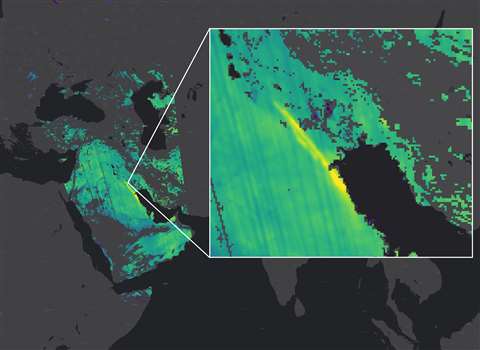

The study estimated the number of large methane leaks that can only be seen from space.

The study estimated the number of large methane leaks that can only be seen from space.

A French climate and energy data analytics company has found a statistical link between oil and gas activities and methane emissions. Kayrros reviewed thousands of satellite images to identify ultra-emitters of methane from sources that cannot be seen from terrestrial monitors.

The company detected between 50 and 150 plumes of methane each month, some of which spread hundreds of kilometers. The study found a direct relationship between ultra-emitters monitored and measured from space and smaller methane leaks detected by local sensors and aircraft surveys.

“Our study supplies a first systematic estimate of large methane leaks that can only be seen from space, showing how these detections relate to wider methane monitoring processes. This is a giant step towards overcoming the current limitations of the methane reporting system which is critical to meeting COP26 commitments to slash methane,” said Kayrros co-founder and scientific director, Alexandre d’Aspremont.

Global oil and gas activities account for at least a fourth of human-made methane emissions, he said, citing recent studies which provide evidence that methane emissions have been widely underestimated by conventional monitoring protocols.

Kayrros data scientists Clement Giron and Matthieu Mazzolini also participated in the study. Other co-authors include Thomas Lauvaux and Philippe Ciais of LSCE, Riley Duren and Daniel Cusworth of Carbon Mapper, and Drew Shindell of Duke University.

The Franco-American team of scientists performed a systematic analysis of thousands of images produced daily by the European Space Agency satellite mission Sentinel-5P to estimate the amount of methane released into the atmosphere by oil and gas production activities in 2019 and 2020.

“The actual number of ultra-emitters varies by country, but the relationship between the number of sources and their magnitude remains the same,” said lead author Thomas Lauvaux, research scientist at the French Climate and Environmental Science Laboratory (Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement, LSCE).

Intermittent emission events of 25 tons per hour or more can only be detected with monitoring satellites, he said. “These huge intermittent events that are normally undetectable consistently account for 8% to 12% of the overall methane emissions from oil and gas activities of any producing country.”

The team used high-resolution atmospheric modelling and machine learning algorithms to detect and quantify hundreds of methane plumes. They then aggregated their emissions estimates at a national scale to evaluate the contribution of ultra-emitters to national reported emissions. To translate their results into a cost-benefit analysis, Shindell performed climate model simulations to quantify the additional contribution to climate change, the company said.

The team detected about 1,800 ultra-emitters (25 t/h or more) over the two years, of which roughly 1,200 come from oil and gas facilities and the remainder from a combination of coal mines, agriculture and waste management. Eliminating these oil-and-gas related events would be tantamount to removing 20 million cars from the road based on the 100-year global warming power (GWP100) of methane, Kayrros said.

The study focused on six major oil and gas producing countries that together account for the majority of ultra-emitters identified through the processing of raw data from the TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) carried by Sentinel-5: Russia, Turkmenistan, USA, Iran, Kazakhstan and Algeria.

The study estimated that oil and gas ultra-emitter represent 8-12% of gas methane emissions from national inventories, a contribution not included in current inventories. It added that eliminating these emissions is easily achievable.

For the first time, the study measured the benefit of eliminating ultra-emitters. Estimates range from $6 billion for Turkmenistan and $4 billion for Russia to $400 million each for Kazakhstan and Algeria.

Only monitoring satellites can systematically detect ultra-emitters. On site sensors and short aerial surveys can only detect smaller leaks, Kayrros said.

“The staggering scale of these ultra-emitters and the huge benefit that would result from their elimination far exceed what we anticipated when Kayrros started investing in the development of our methane watch platform,” said Antoine Rostand, Kayrros president and co-founder.

MAGAZINE

NEWSLETTER

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM